What should your state's bird be?

A whimsical exploration of iNaturalist data

One by one, from 1926 to 1973, the legislature for every U.S. state deliberated carefully to identify their state’s “official bird”. And almost every single legislature got it wrong.

Even in elementary school (the last time knowledge of state birds seemed valuable), it was obvious something was awry. How could it be that so many states chose the same state bird? The states in white at least tried to pick something original, but just two of them managed to choose correctly.

For a more scientific determination of each state’s “official bird,” I turned to a data set of 5 million bird observations uploaded to iNaturalist by citizen-scientists like you. This data included thousands of observations from every state, spanning 1075 bird species.

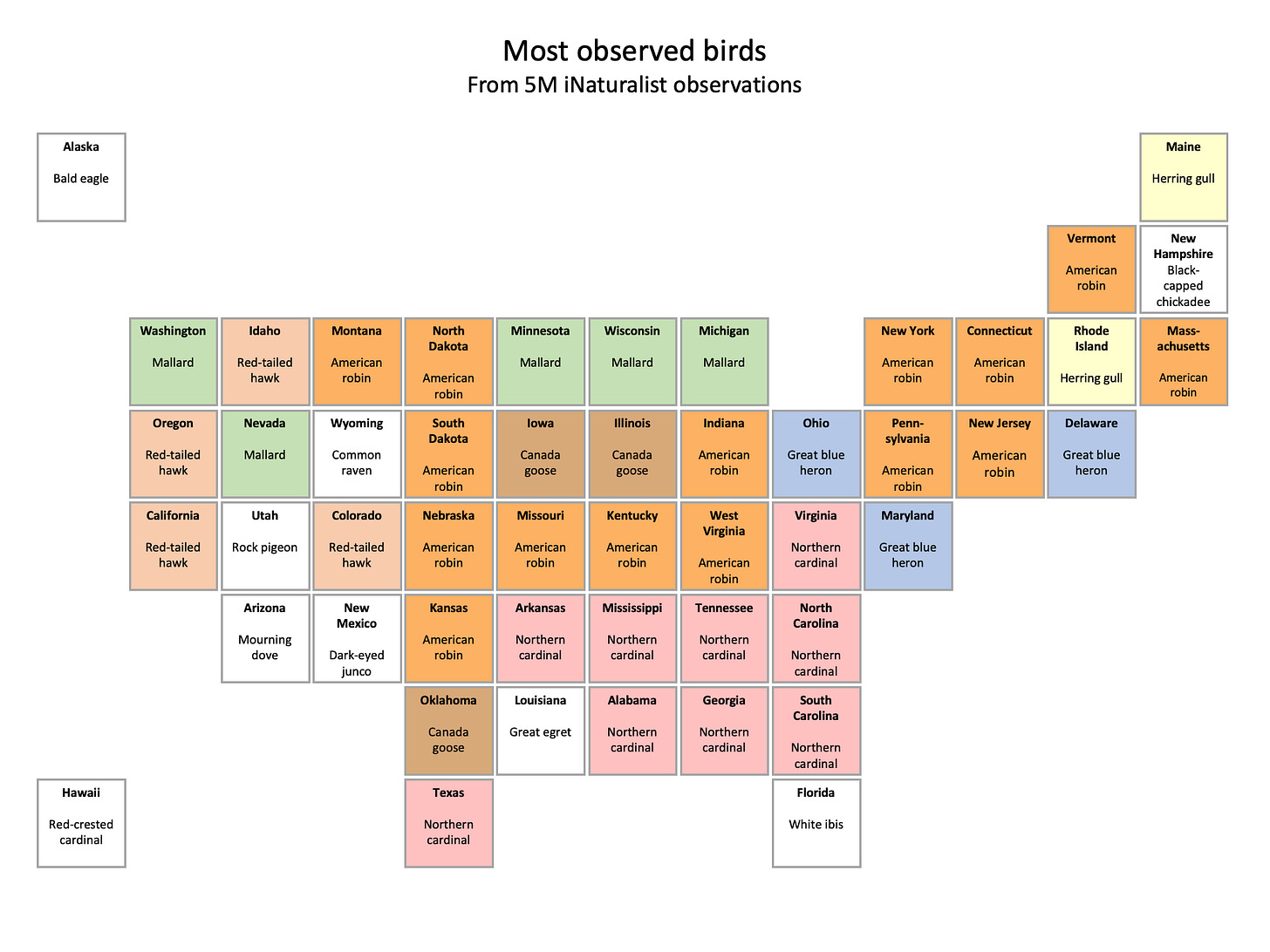

I first checked for the most observed bird in each state:

Overall, it was rare for states to choose their most-observed bird as the state bird (just Connecticut, Virginia, and North Carolina did so). While bird populations may have shifted since the 1926-1973 period, I suspect there’s also an element of “familiarity breeds contempt.” Also, there is an eerie alignment between states where the northern cardinal was the most observed bird and states of the former Confederacy.

Clearly, choosing the most observed bird for each state is not a successful strategy for assigning each state a unique state bird. Instead, I considered the observation frequencies of all bird species within each state. For example, American robins were 5.1% of Nebraska bird observations, a higher proportion than any other state. All 1075 bird species had one state in which their observation frequency was the highest:

Alaska, Florida, Hawaii, and Arizona had the top observation frequencies for the greatest number of bird species. This means that there are many bird species more abundant in those states than any other state. This makes intuitive sense because these four states occupy the geographical and ecological extremes of the country: tundra/forest (Alaska), Caribbean/swamp (Florida), tropical Pacific island (Hawaii), and hot desert (Arizona).

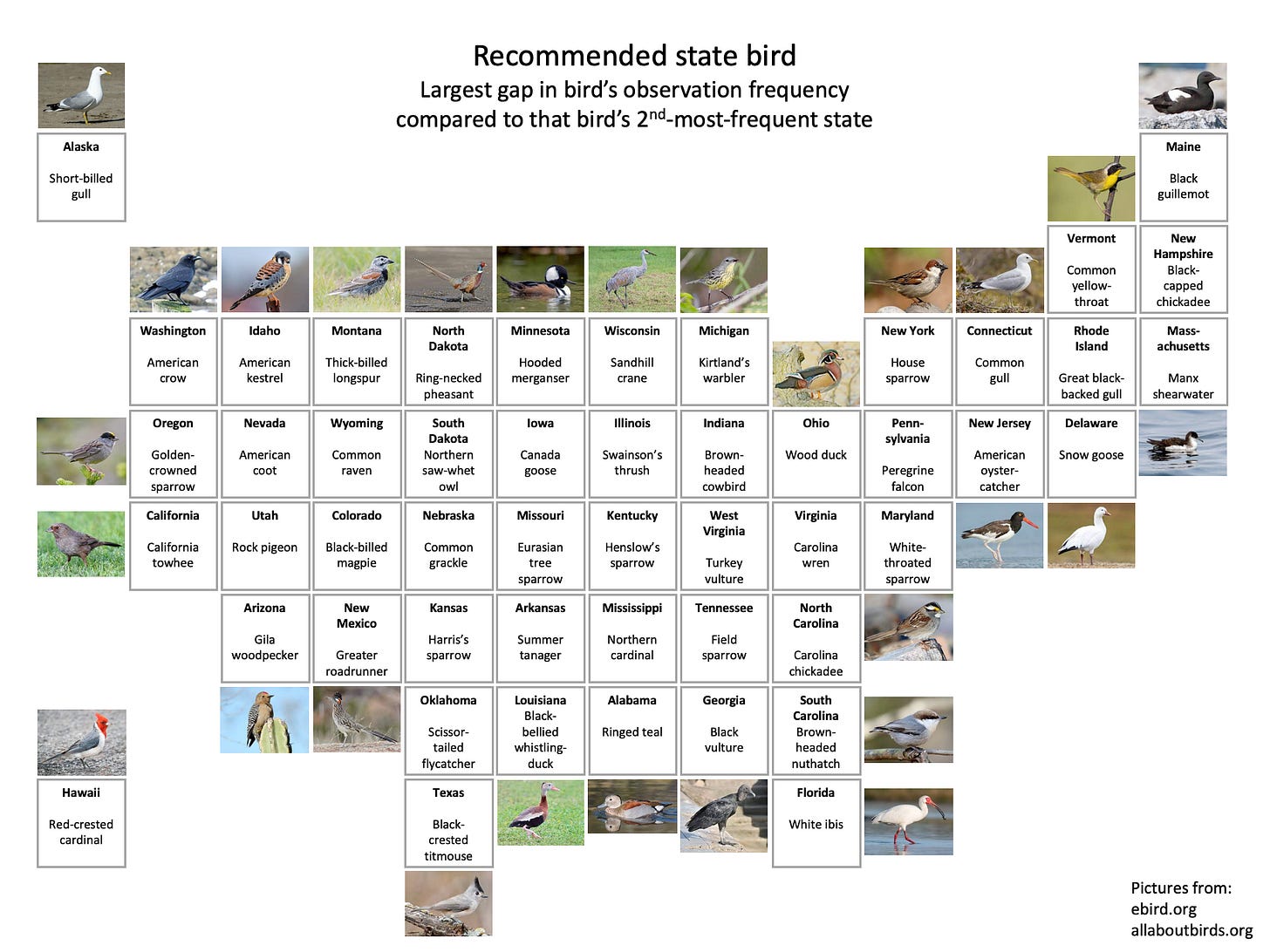

A state’s “official bird” should have higher observation frequency in that state than in any other state. In order to determine the real winner, I looked for the bird species with the biggest gap in observation frequency between the #1 state and the #2 runner-up. For example, American robins were 5.1% of Nebraska’s observations and 5.0% of Massachusetts’s, the 2nd-place state. However, it turns out that common grackles have a more commanding lead in Nebraska versus all other states (2.2% of Nebraskan observations vs. 1.7% of Arkansan observations).

In other words, while the American robin is observed most frequently in Nebraska, the common grackle is in fact the most Nebraskan bird.

This approach yielded a unique bird for each state, which I recommend as the state’s new official bird:

Seven states claimed the northern cardinal as their official bird, but none of those deserve that title - Mississippi does. Similarly, while both Maine and Massachusetts claimed the black-capped chickadee as their official bird, it is in fact their neighbor New Hampshire that deserves that title.

There were two other “steals” in the data set: North Dakota stole the ring-necked pheasant from South Dakota, and Virginia stole the Carolina wren from South Carolina.

Finally, New Mexico’s greater roadrunner and Oklahoma’s scissor-tailed flycatcher were the only two correctly-selected official birds. Congratulations to those two hard-working state legislatures for their careful attention to the science!

As a Wisconsinite, I'm going to agree with sandhill crane is perfect for Wisconsin.

The Northern Cardinal is currently the state bird of Illinois. I think the American Goldfinch would be a good choice for the state bird of Illinois or perhaps, the Eastern Bluebird or even the Western Meadowlark.